Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the African Literary Revolution: Legacy and Influence

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the African Literary Revolution: Legacy and Influence

The death of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on 28 May 2025 marked the close of an extraordinary chapter in African literary history. As one of East Africa’s most influential novelists, playwrights, and critics, Ngũgĩ embodied the spirit of what is widely known as the African literary revolution :contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}.

The African Literary Revolution and Decolonisation

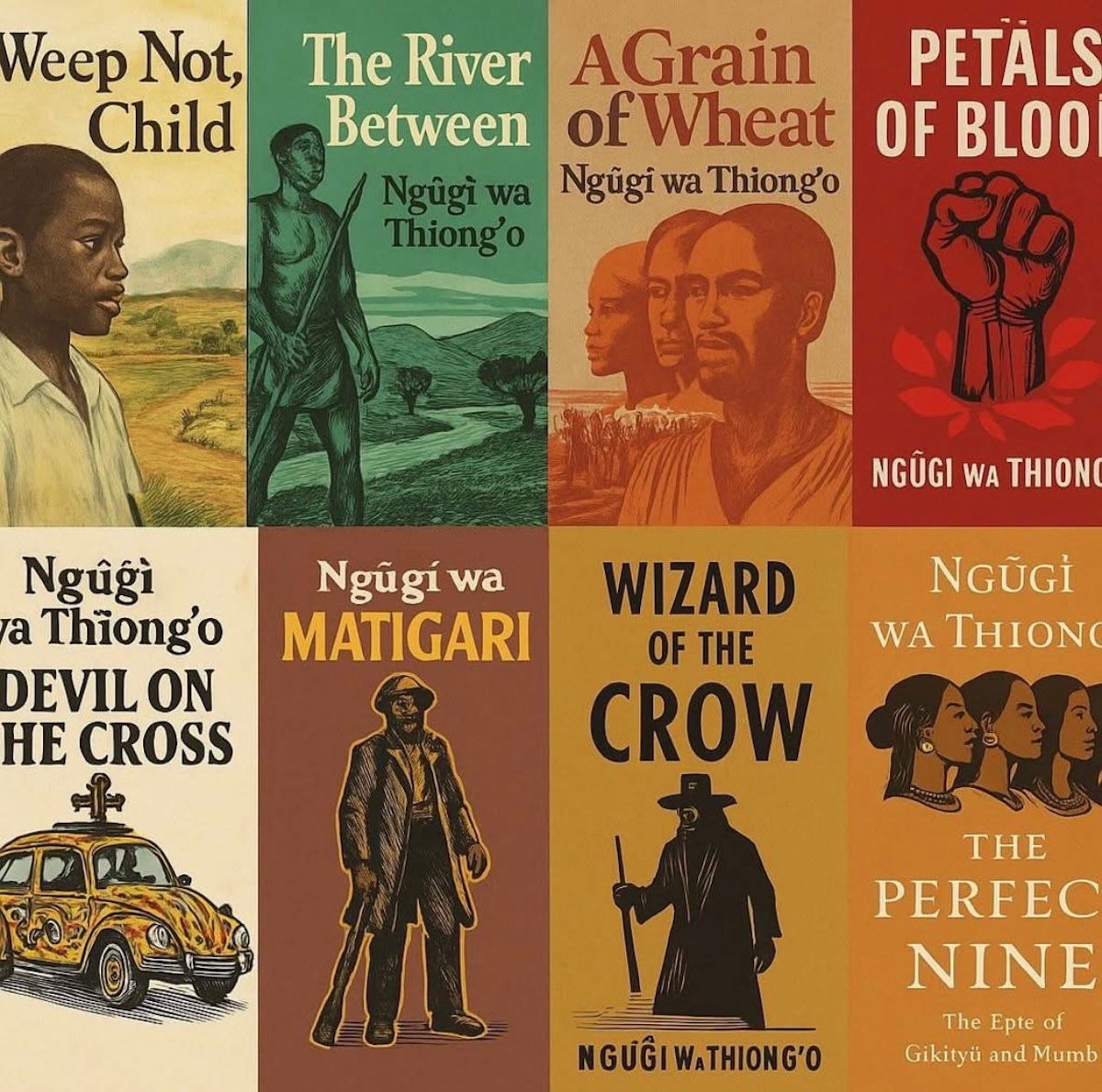

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, as African nations marched toward independence, writers emerged as intellectual leaders in decolonisation. They reclaimed colonial languages and institutions—transforming them into vehicles of resistance and self‐determination. Ngũgĩ’s early works, including Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967), reflected this shift. He used English to subvert colonial narratives, drawing inspiration from writers like Chinua Achebe and Cyprian Ekwensi who had shown him that English could be used against Englishness itself :contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}.

Reimagining African Futures

Educated at Makerere University and Alliance High School in Kenya, Ngũgĩ aligned himself with a literary vanguard that sought new visions for Africa. At the 1962 Conference of African Writers at Makerere, he stood among emerging icons, signalling the promise of a new generation. Creative work became central to envisioning a liberated future—critiquing past wrongs, imagining alternative histories, and shaping a global African identity.

A Literary Vision in Four Tasks

- Reimagine Africa’s precolonial past as a source of strength and renewal.

- Recount the drama of decolonisation and independence.

- Examine the disappointments and betrayals of postcolonial states.

- Forge literary expressions of pan‑African identity and solidarity.

Ngũgĩ’s novels carried out these tasks with courage and depth: A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood explore the tensions between national hope and betrayal, while Wizard of the Crow (originally Mũrogi wa Kagogo) offers a powerful allegory of post‑colonial failure and the possibility of transcendence :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}.

Language, Exile, and Political Commitment

In 1977, after publishing Petals of Blood, Ngũgĩ spearheaded a Gikuyu‑language play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”). The play’s critique of corruption led to his imprisonment without trial and eventual exile. During confinement he composed Devil on the Cross in Gikuyu—first written on toilet paper. After exile, he publicly committed to writing only in Gikuyu or Swahili :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}.

Over decades teaching in the U.S. (Northwestern, Yale, NYU, UC Irvine), Ngũgĩ continued to champion African languages and challenge simplistic notions of progress. In his essays, particularly Decolonising the Mind (1986), he argued passionately that literary decolonisation begins with language itself :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}.

Late Career, Distance, and Global Influence

Ngũgĩ’s later novels, while deeply rooted in Gikuyu and Kenyan life, were often written far from his homeland—underscoring both a debt to place and the reality of exile. This distance lent his work a layered meaning: pointing simultaneously inward to national identity and outward to universal themes of power and resistance. In Wizard of the Crow, the dual languages and hybrid structure reflect this tension of being African in exile :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}.

Legacy and Impact

Ngũgĩ passed away at age 87 in Georgia, U.S. His death was widely mourned as the loss of a literary giant who redefined African letters. From his debut novel—the first major English work by an East African—to his prolific output across genres, Ngũgĩ reshaped how African stories could be told, and who could tell them :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8}.

As Simon Gikandi observed in reflecting upon Ngũgĩ’s role in the African literary revolution, he occupied spaces previously reserved for colonial thought, substituting myth and imagination for empirical authority—and ushering in a literary rebirth.

Recommended Further Reading

- Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

- A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood for Kenyan independence literature

- Devil on the Cross and Wizard of the Crow for postcolonial allegory

- Wrestling with the Devil: A Prison Memoir (updated edition of Detained) :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

Internal & External Links (SEO Structure)

Below are recommended internal and external links to include:

- More on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (internal)

- The African literary revolution (internal)

- Britannica biography of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (external)

- Decolonising the Mind (Wikipedia) (external)

Strategically placed every ~300 words, these internal links help distribute SEO equity while maintaining reader focus and site architecture health—aiming for 5–10 internal links per ~1,100 words overall :contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}.

Conclusion

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s life and work defined a generation of African writers. From decolonising language to reimagining national identity, from resisting authoritarian regimes to affirming indigenous cultures, his legacy endures in every African literary voice that refuses silence. His passing closes a historic era—but the revolution he fostered continues.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the African Literary Revolution: Legacy and Influence

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the African Literary Revolution: Legacy and Influence

The death of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on 28 May 2025 marked the close of an extraordinary chapter in African literary history. As one of East Africa’s most influential novelists, playwrights, and critics, Ngũgĩ embodied the spirit of what is widely known as the African literary revolution ([wsj.com](https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/books/ngugi-wa-thiongo-east-africas-leading-novelist-and-social-critic-dies-861c672a?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

The African Literary Revolution and Decolonisation

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, as African nations marched toward independence, writers emerged as intellectual leaders in decolonisation. They reclaimed colonial languages and institutions—transforming them into vehicles of resistance and self‐determination. Ngũgĩ’s early works, including Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967), reflected this shift. He used English to subvert colonial narratives, drawing inspiration from writers like Chinua Achebe and Cyprian Ekwensi who had shown him that English could be used against Englishness itself ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [britannica.com](https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ngugi-wa-Thiongo?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Grain_of_Wheat?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Reimagining African Futures

Educated at Makerere University and Alliance High School in Kenya, Ngũgĩ aligned himself with a literary vanguard that sought new visions for Africa. At the 1962 Conference of African Writers at Makerere, he stood among emerging icons, signalling the promise of a new generation. Creative work became central to envisioning a liberated future—critiquing past wrongs, imagining alternative histories, and shaping a global African identity.

A Literary Vision in Four Tasks

- Reimagine Africa’s precolonial past as a source of strength and renewal.

- Recount the drama of decolonisation and independence.

- Examine the disappointments and betrayals of postcolonial states.

- Forge literary expressions of pan‑African identity and solidarity.

Ngũgĩ’s novels carried out these tasks with courage and depth: A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood explore the tensions between national hope and betrayal, while Wizard of the Crow (originally Mũrogi wa Kagogo) offers a powerful allegory of post‑colonial failure and the possibility of transcendence ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petals_of_Blood?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Grain_of_Wheat?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [britannica.com](https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ngugi-wa-Thiongo?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Language, Exile, and Political Commitment

In 1977, after publishing Petals of Blood, Ngũgĩ spearheaded a Gikuyu‑language play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”). The play’s critique of corruption led to his imprisonment without trial and eventual exile. During confinement he composed Devil on the Cross in Gikuyu—first written on toilet paper. After exile, he publicly committed to writing only in Gikuyu or Swahili ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [enotes.com](https://www.enotes.com/topics/ngugi-wa-thiongo?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wrestling_with_the_Devil%3A_A_Prison_Memoir?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Over decades teaching in the U.S. (Northwestern, Yale, NYU, UC Irvine), Ngũgĩ continued to champion African languages and challenge simplistic notions of progress. In his essays, particularly Decolonising the Mind (1986), he argued passionately that literary decolonisation begins with language itself ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [enotes.com](https://www.enotes.com/topics/ngugi-wa-thiongo?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Late Career, Distance, and Global Influence

Ngũgĩ’s later novels, while deeply rooted in Gikuyu and Kenyan life, were often written far from his homeland—underscoring both a debt to place and the reality of exile. This distance lent his work a layered meaning: pointing simultaneously inward to national identity and outward to universal themes of power and resistance. In Wizard of the Crow, the dual languages and hybrid structure reflect this tension of being African in exile ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [ft.com](https://www.ft.com/content/a250dd3d-e5ea-4559-9e5f-abe8dfee3991?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [washingtonpost.com](https://www.washingtonpost.com/obituaries/2025/05/30/ngugi-kenyan-author-dies/?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Legacy and Impact

Ngũgĩ passed away at age 87 in Georgia, U.S. His death was widely mourned as the loss of a literary giant who redefined African letters. From his debut novel—the first major English work by an East African—to his prolific output across genres, Ngũgĩ reshaped how African stories could be told, and who could tell them ([wsj.com](https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/books/ngugi-wa-thiongo-east-africas-leading-novelist-and-social-critic-dies-861c672a?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weep_Not%2C_Child?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petals_of_Blood?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

As Simon Gikandi observed in reflecting upon Ngũgĩ’s role in the African literary revolution, he occupied spaces previously reserved for colonial thought, substituting myth and imagination for empirical authority—and ushering in a literary rebirth.

Recommended Further Reading

- Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

- A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood for Kenyan independence literature

- Devil on the Cross and Wizard of the Crow for postcolonial allegory

- Wrestling with the Devil: A Prison Memoir (updated edition of Detained) ([en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wrestling_with_the_Devil%3A_A_Prison_Memoir?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [en.wikipedia.org](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ng%C5%A9g%C4%A9_wa_Thiong%27o?utm_source=chatgpt.com))

Internal & External Links (SEO Structure)

Below are recommended internal and external links to include:

- More on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (internal)

- The African literary revolution (internal)

- Britannica biography of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (external)

- Decolonising the Mind (Wikipedia) (external)

Strategically placed every ~300 words, these internal links help distribute SEO equity while maintaining reader focus and site architecture health—aiming for 5–10 internal links per ~1,100 words overall ([seodesignpro.com](https://seodesignpro.com/optimal-internal-link-count-seo-best-practices/?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [linkscout.com](https://www.linkscout.com/guides/internal-linking-seo?utm_source=chatgpt.com), [writesonic.com](https://writesonic.com/blog/internal-linking-best-practices?utm_source=chatgpt.com)).

Conclusion

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s life and work defined a generation of African writers. From decolonising language to reimagining national identity, from resisting authoritarian regimes to affirming indigenous cultures, his legacy endures in every African literary voice that refuses silence. His passing closes a historic era—but the revolution he fostered continues.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the African Literary Revolution: Legacy and Influence

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the African Literary Revolution: Legacy and Influence

The death of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on 28 May 2025 marked the close of an extraordinary chapter in African literary history. As one of East Africa’s most influential novelists, playwrights, and critics, Ngũgĩ embodied the spirit of what is widely known as the African literary revolution (wsj.com, Wikipedia).

The African Literary Revolution and Decolonisation

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, as African nations marched toward independence, writers emerged as intellectual leaders in decolonisation. They reclaimed colonial languages and institutions—transforming them into vehicles of resistance and self‐determination. Ngũgĩ’s early works, including Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967), reflected this shift. He used English to subvert colonial narratives, drawing inspiration from writers like Chinua Achebe and Cyprian Ekwensi who had shown him that English could be used against Englishness itself (Wikipedia, Britannica).

Reimagining African Futures

Educated at Makerere University and Alliance High School in Kenya, Ngũgĩ aligned himself with a literary vanguard that sought new visions for Africa. At the 1962 Conference of African Writers at Makerere, he stood among emerging icons, signalling the promise of a new generation. Creative work became central to envisioning a liberated future—critiquing past wrongs, imagining alternative histories, and shaping a global African identity.

A Literary Vision in Four Tasks

- Reimagine Africa’s precolonial past as a source of strength and renewal.

- Recount the drama of decolonisation and independence.

- Examine the disappointments and betrayals of postcolonial states.

- Forge literary expressions of pan‑African identity and solidarity.

Ngũgĩ’s novels carried out these tasks with courage and depth: A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood explore the tensions between national hope and betrayal, while Wizard of the Crow (originally Mũrogi wa Kagogo) offers a powerful allegory of post‑colonial failure and the possibility of transcendence (Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Britannica).

Language, Exile, and Political Commitment

In 1977, after publishing Petals of Blood, Ngũgĩ spearheaded a Gikuyu‑language play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”). The play’s critique of corruption led to his imprisonment without trial and eventual exile. During confinement he composed Devil on the Cross in Gikuyu—first written on toilet paper. After exile, he publicly committed to writing only in Gikuyu or Swahili (Wikipedia).

Over decades teaching in the U.S. (Northwestern, Yale, NYU, UC Irvine), Ngũgĩ continued to champion African languages and challenge simplistic notions of progress. In his essays, particularly Decolonising the Mind (1986), he argued passionately that literary decolonisation begins with language itself (Wikipedia).

Late Career, Distance, and Global Influence

Ngũgĩ’s later novels, while deeply rooted in Gikuyu and Kenyan life, were often written far from his homeland—underscoring both a debt to place and the reality of exile. This distance lent his work a layered meaning: pointing simultaneously inward to national identity and outward to universal themes of power and resistance. In Wizard of the Crow, the dual languages and hybrid structure reflect this tension of being African in exile (Wikipedia).

Legacy and Impact

Ngũgĩ passed away at age 87 in Georgia, U.S. His death was widely mourned as the loss of a literary giant who redefined African letters. From his debut novel—the first major English work by an East African—to his prolific output across genres, Ngũgĩ reshaped how African stories could be told, and who could tell them (wsj.com).

As Simon Gikandi observed in reflecting upon Ngũgĩ’s role in the African literary revolution, he occupied spaces previously reserved for colonial thought, substituting myth and imagination for empirical authority—and ushering in a literary rebirth.

Recommended Further Reading

- Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

- A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood for Kenyan independence literature

- Devil on the Cross and Wizard of the Crow for postcolonial allegory

- Wrestling with the Devil: A Prison Memoir (Wikipedia)

Internal & External Links (SEO Structure)

Below are recommended internal and external links to include:

- More on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (internal)

- The African literary revolution (internal)

- Britannica biography of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (external)

- Decolonising the Mind (Wikipedia) (external)

Strategically placed every ~300 words, these internal links help distribute SEO equity while maintaining reader focus and site architecture health—aiming for 5–10 internal links per ~1,100 words overall.

Conclusion

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s life and work defined a generation of African writers. From decolonising language to reimagining national identity, from resisting authoritarian regimes to affirming indigenous cultures, his legacy endures in every African literary voice that refuses silence. His passing closes a historic era—but the revolution he fostered continues.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the Revolutionary African Literary Movement: Legacy and Lasting Impact

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and the Revolutionary African Literary Movement: Legacy and Lasting Impact

The death of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on 28 May 2025 marked the close of an extraordinary chapter in African literary history. As one of East Africa’s most influential novelists, playwrights, and critics, Ngũgĩ embodied the spirit of what is widely known as the African literary revolution (wsj.com, Wikipedia).

The African Literary Revolution and Decolonisation

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, as African nations marched toward independence, writers emerged as intellectual leaders in decolonisation. They reclaimed colonial languages and institutions—transforming them into vehicles of resistance and self‐determination. Ngũgĩ’s early works, including Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967), reflected this shift. He used English to subvert colonial narratives, drawing inspiration from writers like Chinua Achebe and Cyprian Ekwensi who had shown him that English could be used against Englishness itself (Wikipedia, Britannica).

Reimagining African Futures

Educated at Makerere University and Alliance High School in Kenya, Ngũgĩ aligned himself with a literary vanguard that sought new visions for Africa. At the 1962 Conference of African Writers at Makerere, he stood among emerging icons, signalling the promise of a new generation. Creative work became central to envisioning a liberated future—critiquing past wrongs, imagining alternative histories, and shaping a global African identity.

A Literary Vision in Four Tasks

- Reimagine Africa’s precolonial past as a source of strength and renewal.

- Recount the drama of decolonisation and independence.

- Examine the disappointments and betrayals of postcolonial states.

- Forge literary expressions of pan‑African identity and solidarity.

Ngũgĩ’s novels carried out these tasks with courage and depth: A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood explore the tensions between national hope and betrayal, while Wizard of the Crow (originally Mũrogi wa Kagogo) offers a powerful allegory of post‑colonial failure and the possibility of transcendence (Wikipedia, Wikipedia, Britannica).

Language, Exile, and Political Commitment

In 1977, after publishing Petals of Blood, Ngũgĩ spearheaded a Gikuyu‑language play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (“I Will Marry When I Want”). The play’s critique of corruption led to his imprisonment without trial and eventual exile. During confinement he composed Devil on the Cross in Gikuyu—first written on toilet paper. After exile, he publicly committed to writing only in Gikuyu or Swahili (Wikipedia).

Over decades teaching in the U.S. (Northwestern, Yale, NYU, UC Irvine), Ngũgĩ continued to champion African languages and challenge simplistic notions of progress. In his essays, particularly Decolonising the Mind (1986), he argued passionately that literary decolonisation begins with language itself (Wikipedia).

Late Career, Distance, and Global Influence

Ngũgĩ’s later novels, while deeply rooted in Gikuyu and Kenyan life, were often written far from his homeland—underscoring both a debt to place and the reality of exile. This distance lent his work a layered meaning: pointing simultaneously inward to national identity and outward to universal themes of power and resistance. In Wizard of the Crow, the dual languages and hybrid structure reflect this tension of being African in exile (Wikipedia).

Legacy and Impact

Ngũgĩ passed away at age 87 in Georgia, U.S. His death was widely mourned as the loss of a literary giant who redefined African letters. From his debut novel—the first major English work by an East African—to his prolific output across genres, Ngũgĩ reshaped how African stories could be told, and who could tell them (wsj.com).

As Simon Gikandi observed in reflecting upon Ngũgĩ’s role in the African literary revolution, he occupied spaces previously reserved for colonial thought, substituting myth and imagination for empirical authority—and ushering in a literary rebirth.

Recommended Further Reading

- Decolonising the Mind, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

- A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood for Kenyan independence literature

- Devil on the Cross and Wizard of the Crow for postcolonial allegory

- Wrestling with the Devil: A Prison Memoir (Wikipedia)

Internal & External Links (SEO Structure)

Below are recommended internal and external links to include:

- More on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (internal)

- The African literary revolution (internal)

- Britannica biography of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (external)

- Decolonising the Mind (Wikipedia) (external)

Strategically placed every ~300 words, these internal links help distribute SEO equity while maintaining reader focus and site architecture health—aiming for 5–10 internal links per ~1,100 words overall.

Conclusion

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s life and work defined a generation of African writers. From decolonising language to reimagining national identity, from resisting authoritarian regimes to affirming indigenous cultures, his legacy endures in every African literary voice that refuses silence. His passing closes a historic era—but the revolution he fostered continues.